From "The fishing gazette" - June 28th, 1884

THAT natural hackles must sooner or later come into fashion, seems to me to be a foregone conclusion; so many are the advantages we derive from them, that it is almos suprising the old standard patterns are having such a long day. Only half the amount of feather is required, and therefore boddies of flies are not so liable to be clogged with superfluous material, which always tends to skirt the water. Moreover, they never fade, and if they happen to loose a trifle of their brilliancy, it is so infintesimal that their value practically does not suffer. They rarely change appearance in the water like the others. And we can shift them from old flies to new without sacrificing more than the four or five fibres, which would otherwise be stripped off for a hook one size less. Our tinsels and lace do not become tarnished by coming in contact with some injurious chemical from the dyer's mixture; and they are also superior, because they are more fatally attractive, which, though mentioned last, should be the primary consideration.

There is no work that I am aware of which enters with any fulness in a true and practical manner into the subject-matter of these articles. Those amateurs whose studies in the language of feathers have been fuller and riper than my own - those who admire the art of flydressing merely for its own sake - would surely wish to see its elements made accessible to all salmon fishermen, were it only that they may be the more thouroughly examined into, and therefore the more effectually developed. I purpose after the hackle question is ventilated, to make some allusions to the subject from the beginning to the end; perhaps from the legs to the bodies upon which these plumes are placed. I have elected to take this step since skimming that genius, "Blacker," which book has been kindly sent up by Mr. Marson.

The instruction it contains for whipping up flies, to use a mild term, is rubbish. I was under the impression "Blacker on Flies" was a great work. His reputation was decidedly great, but in the three attributes of genius, feeling and perseverance reigned apparently in such profusion, that understanding must have been left out in the cold.

The multitude of somewhat similar books of this description which modern readers wade through may produce distraction as much as culture, the process leaving no more definite impression upon the mind than gazing through the shifting forms in a kaleidoscope does upon the eye. Reading is often but a mere passive reception of other men's thoughts, there being little or no active effort of the mind in the transaction. Then how much of our reading is but the indulgence of a sort of exitement for the moment only, without the slightest effect in improving us? It is really useless to tell the uninitiated "to get a bit of feather and tie it on a hook"; you might as well give them an order from a "Brum" or a "Chat," and expect to receive the contact note.

Upon this subject, I quite think the time has arrived for a new road of observation, attention, and industry.

Is it not impossible for the tyro to "see through" a salmon fly? And many of us are even apt to fall into the extreme of condemning anything in this commodity which is modern, and estimating too highly the value of past produce.

Perhaps it is not always necessary to make flies as evenly and perfectly as the representation in our illustration; but I do wish to urge that when salmon are hard to please, - when twenty rods are at work and about a couple of the "infallibles" walk home with a fish; it is invariably the master hands, - those who know how to make and how to use the fly, - those who intuitively put justs the amout of material, and no more, on the hook in the right place, as to make the lure swim so truly, so temptingly, that even the sulky salmon on the most unlikely day is moved into activity.

"A fly to fish well, and how to make it," would possibly interest some of my readers, and this would be an interesting subject from time to time, as I wend my way for the future.

We now and then hear of salmon being taken "on the rough," making use of a hackneyed expression, when the fly is not fished, but snatched over the catch; the line making "duck trails" on the surface while the bait below is engaged in acrobatic performances. Only last year, at Ringwood, Co. B., passing from pool to pool wetting an "Eagle" in eighteen inches of water, hooked and gaffed a 42lb. fresh-run fish. This season, in Lady Mill's water, on the Test, after a monster had just acknowledged two offers from Mr., B. F., one of the best anglers and fly makers living, accepted from this gentleman a giant "blue jay" (local name, something after the blue Doctor, with jay feather cheeks), and was lugged out under a scorching sun in the middle of the day. I know this pretty little bit of drawingroom fishing well from the opposite bank; and in spring it is usually haunted by magnificent salmon; the average this year is upwards of 30 lb. for forty fish.

So it will be seen that there is another exception to the rule; but one can scarcely be too particular in the management of seal's fur feather, and hackle, either in the workshop, or afterwards when worked over a catch.

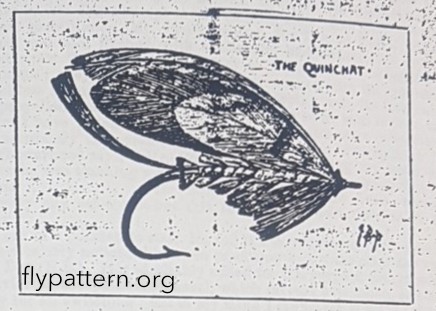

The fly that illustrate this week is a picture. The customary charm of harmony is most favourably expressed. It is rather a difficult fly to dress to swim truly, but such obstacles vanish before determined effort.

Quinchat is well worth a deal of painstaking. It is another fly that is better dressed large, and therefore not a summer pattern anywhere, but would be a splendid change in every district.

It is described:-

Tag: Silver twist, and purple silk (same shade as throat of blue chatterer).

Tail: Topping.

Butt: Black herl.

Body: In five sections, each increasing in length as illustrated. The first part is red silk, the same shade as the points of the red crow; one of these feathers, it will be observed, is above and below. The remanining four divisions are light blue silk, the same colour as the light blue chatterer hackles at the termination of the second and third partition. (These feathers are from the top of the tail.) At the end of the fourth and fifth division the hackles are light blue mackaw.

Ribbed: Oval tinsel.

Throat: Yellow macaw (flank feather).

Wings: Two blue mackaw feathers. The feathers which are over them (extended cheeks) are green macaw.

Cheeks: Indian (red) crow. Two toppings over.

Horns: Red macaw (double).

Head: Black herl.

I have never tried it, and, therefore, say but little; but of this fly rumour runs high, accrediting it with having killed five heavy salmon before sunset one evening, and nearly settling five men before the sun rose. We may assume that the chat of the quintette was joyuous and festive indeed.

Fishermen may chiefly be attracted by its brilliance, its beauty; if a fly can be too beautiful, it is a charming blemish in bright weather.

However, it presents the same features of intimate knowledge, and carefulness of detail which characterised those which preceded it, and is destined to become a great favourite in the spring of the year.

My description is somewhat irregular, but I have worded it so that it may read easier to young dressers.

"Quinchat" may be purchased at the same firms I have mentioned heretofore. -----

Thanks to Todd Kennedy - "Jock Scott", for providing a copy of the original article for this pattern.

|