From "The fishing gazette" - August 9th, 1884

SPREADING tails, sometimes flat, sometimes in set-sail fashion, resembling closed butterflies' wings, are very effective and telling. I am very partial to them seated erect on any of the "Baker" element; but they would be out of character and ill-placed on any of these more refined patterns. Almost every wing feather in our collection can be utilised here in moderation; and if we want this sort of tail bow-shaped - turning up like the illustration - the strands from one side should be piled first and backed with those from the other; but after collecting the whole bundle, we must be careful in replacing any that are obstinate or reversed, before they are attached.

Mixed at will, they may be rolled between the thumb and forefinger, but not twisted, taking pains beforehand to pack them pretty much the same length. Unless it is first-class work, we may frequently observe that these fibres have been incorrectly fastened, resulting in a projection just at the very place where the small part of the taper should start from. But it is simple enough to avoid this obstruction.

You remember you have already levelled the under part with the floss which meets the gut, and that on the top from here there is nothing but the even and regular coils of tying silk closely woven. As a formal example, take Teal, Canadian duck, Gallina, Ibis, yellow Macaw, powdered blue, and Tippet, a minute portion of the three former, laying the latter only in different lengths, though also in single strands. Such combination would make a splendid show. In order to escape this clumsy lump, which is a dreadful eyesore, begin by lashing on the tail with a couple of turns of silk, holding the fibres between the thumb and forefinger for the upright variety; but if "shovel-tailed," merely press the thumb down throughout the work over them after they have been spread to suit the fancy. In cutting the waste away hold the scissors along, not across, the hook, and fetch it off pretty close to the iron, just touching the remainder with varnish before it is made secure with another turn or two of the silk. The herl butt should cover enough for you to have a fair road to proceed; but bear in mind that the scissors have encouraged the taper to decrease the wrong way, which momentary mischief you override by winding the small sprays or point of a rapid-tapered hell over the part apparently a little thick, and following on with its fuller ones to make up the very slight descent.

Particulars such as these, and many others to which I may occasionally allude, are more for amateurs who have "gone through the mill," who know something of the work and who aim at nothing short of perfection.

Professionals can scarcely be expected to resort to such measures - they could ill afford the time, especially at their present prices. Hence our work is reputed to be firmer, truer, and more to be depended upon; but, of course. I am not alluding to the specimens of those who are masters of the art.

It is in these first steps, these early stages, that we require to be careful before we can possibly spring up enlightenment; and we must trace, we must pave these less interesting yet all important subways, by which alone we reach the goal.

If we really desire to gain habitual confidence - to become proficient, we should keep up our practice; there is no art in fly-dressing that is too difficult for industry to attain to. Industry makes its science easy; but that systematic knowledge founded on principles so infinite which to us has such a fascination, soon becomes so distasteful from the mere custom of inactivity that we are liable to sink from one state of quiescence into another till we may finally forget the most trivial matters which we have accomplished previous with the outmost ease.

However clever we may be, or however much we may know of flies, we can never decide what salmon take them for. Some schools say seaweed; other, for enemies or opponents on the spawning bed. Many authors tell us that this fish does not feed in fresh water; if we are to believe them, flies cannot be fancied for food. Have any of my readers ever seen salmon take caterpillaars that have fallen from overhanging bushes? I have. Butterflies, struggling for their lives on the surface of the stream; wasps, as they dip like martins and swallows; dragon flies, as they flit along the sedgy side. I have also seen kelts chivying pinks and swallow them; and to they not readily take our worm, legering? or when in its steady and undisturbed descent down a flat suspended below our float yards and yards from the point of the rod? But the authors add that, of all the thousands of Salmon opened annyally, not one single atom of food is ever found in their stomachs.

Some years ago, pike fishing about Christmas time, I took my casting net to a favorite little rivulet (an upper tributary to a well-known salmon river) for a pitch over the numberless small yellow trout always to be seen there. In arranging the meshes over one shoulder I was gently tapped on the other by the water bailif. "I see you have my master's dog, sir; do you mean having the salmon too?" he asked

The "master," however, was a peaceful relative of mine, and "Shot," the pointer, with only a hale, hearty old housekeeper of perhaps seventy summers, whose profusion of respected wrinkles almost as regular as the jowl of a jack, had been my companions for some few days; the dog just now was made fast to a fence.

The "Artful Dodger" - such was the keeper's village title - was, however, soon satisfied, and called my attention to a salmon in a miniature pool of water, bright as gin, and only 18in deep. The back fin of a trout quite 1/2lb. was at that moment ploughing its way up stream over the peeping pebbles at the outlet; it could thus scramble in, but the salmon - or rather the two salmon, for the female was also there - could neither get up nor down. He was devoting his attention to the persistent little trout which would not be beaten off, and which seemed bent upon disturbing her ladyship, who was busily engaged over a bright little dip in the gravelly bottom. At last we distinctly saw the trout caught and devoured. A friend who had just then put in an appearance determined to have this fish "set up"; the casting net was immediately popped over, and a 25lb. salmon was dragged out on to the bank in a moment. It proved to be dreadfully diseased, so we decided to dissect it, and found the cankerous sores little more than skin deep. But where was the trout? Nowhere. In the stomach? Not a sign of it; neither did we ever know!

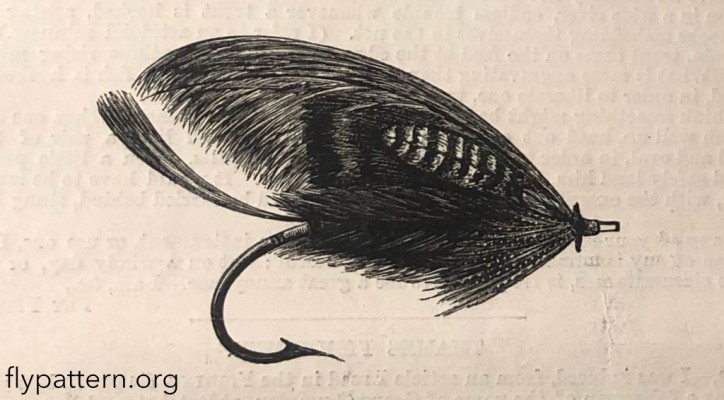

. . . . The fly that I illustrate this week, with its beautiful blue body, is one of the most useful, one of the most expensive, and one of the most difficult to dress - indeed, a trophy which should specially attract our attention, and rise us into action in our wakeful study. The amateur who can make a fairly good "chatterer" anything approaching the illustration in shape may be regarded as a prodigy of skill and patience.

Such a device, the fruitful result of experience, the acme of perfection, may well suggest something beyond the mere picture of fancy - may mean more than an idea germinated and matured from the screened seed of knowledge - might almost strike us as nothing less than the ideal insect of superlative and Oriental beauty, or a clever copy of some sylph-like splendor looming from a magic lens - in either case vividly and most truthfully portrayed.

There is not a little generalship required in managing and marshalling some seven or eight dozen of these delicate and brilliant feathers - two at a time, one over the other - to form a true taper the whole length of the body ; neither is it a task an angler would care to undertake before breakfast. But to give anything like an idea to the uninitiated of this charming invention and work of one who has every fancy feather at hand ready for his facile fingers, we want color, or better still, the original fly. The "chatterer" can be made two ways - by padding the body and using the same sized feathers all along, or by increasing the length of them as you progress; your assortment, however, must be an extensive one, and if you select those of uniform dimensions the fibres will be more regular in substance, more even in action, and consequently more shapely under water. It is described :-

Tag: Silver twist and light orange floss (tippet colour).

Tail: Topping.

Butt: Black herl.

Body: Two turns of purple silk, making headway for the chatterer's feathers closely packed and covering the whole of the body. A hook this size taking perhaps fifty to sixty.

Throat: Gallina.

Wings: Four red crows, in pairs, red pints of the former extended, and one jay feather on either side. Toppings over.

Cheeks: Blue Chatterer.

Horns: Blue macaw.

Head: Black herl.

|